The NZIA Injection Capacity Obligation: What does it mean for European carbon management development?

Europe is accelerating its industrial transformation for net-zero, backed now by binding legislation. One year after its adoption, the Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) is moving from targets to concrete legal obligations. Building upon the foundations set by the European Climate Law, which enshrines a 55% emissions reduction target by 2030 and climate neutrality by 2050, the NZIA aims to make the European Union (EU) a global hub for clean technology manufacturing and decarbonise the industrial sectors. For carbon capture and storage (CCS), the NZIA places developing CO₂ infrastructure at the heart of the EU’s emerging clean industrial policy.

The NZIA: A key cornerstone of the EU industrial carbon management policy framework

First proposed in March 2023, the NZIA is designed to strengthen the resilience of the Union energy system, reduce reliance on imported technologies, and enable the EU to achieve its climate targets. It supports this by streamlining permitting procedures and reducing administrative burdens for strategic net-zero technologies, including CCS.

A cornerstone of the NZIA is Chapter 3, which is devoted specifically to advancing CO₂ storage and does so in three key ways:

- First, Article 20 establishes a legally binding target of achieving at least 50 million tonnes of annual CO₂ injection capacity by 2030.

- Second, Article 21 requires Member States to submit annual reports on CO₂ storage capacity data. These reports are comprehensive, including the mapping of CO₂ capture, transport, and storage projects, as well as information on existing and planned national support measures, strategies, and targets. This reporting framework functions not only as a compliance mechanism, supporting the Commission’s monitoring and market assessment reports, but also as a vital transparency tool. By making this information publicly accessible, the NZIA empowers a wide range of stakeholders to monitor and assess progress toward the Union-wide CO₂ injection capacity target.

- Finally, Article 23 places an obligation on oil and gas producers to contribute to the Union CO₂ injection capacity objective by 2030, positioning them as key developers in advancing the EU’s carbon storage industry. Each individual contribution is calculated pro rata based on their share in the EU’s oil and natural gas production between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2023. Complementary to this, Article 23 also requires obligated entities to submit a plan by 30 June 2025 outlining how they intend to meet their individual target and an annual progress report from 2026 onwards.

The Injection Capacity Obligation (ICO) mechanism: what it means, and what is needed to ensure its effectiveness

As part of the implementation of such obligation, the European Commission has recently adopted a Decision disclosing the list of 44 obligated entities, marking a key step in the operationalisation of Article 23. This raises important questions about who is obligated, who was excluded, and what this could mean for the future of CO₂ storage development in Europe.

Here are five takeaways on the Injection Capacity Obligation (ICO) mechanism, what it means, and what is needed to ensure its effectiveness.

1. Setting the exemption threshold: balancing fairness and impact

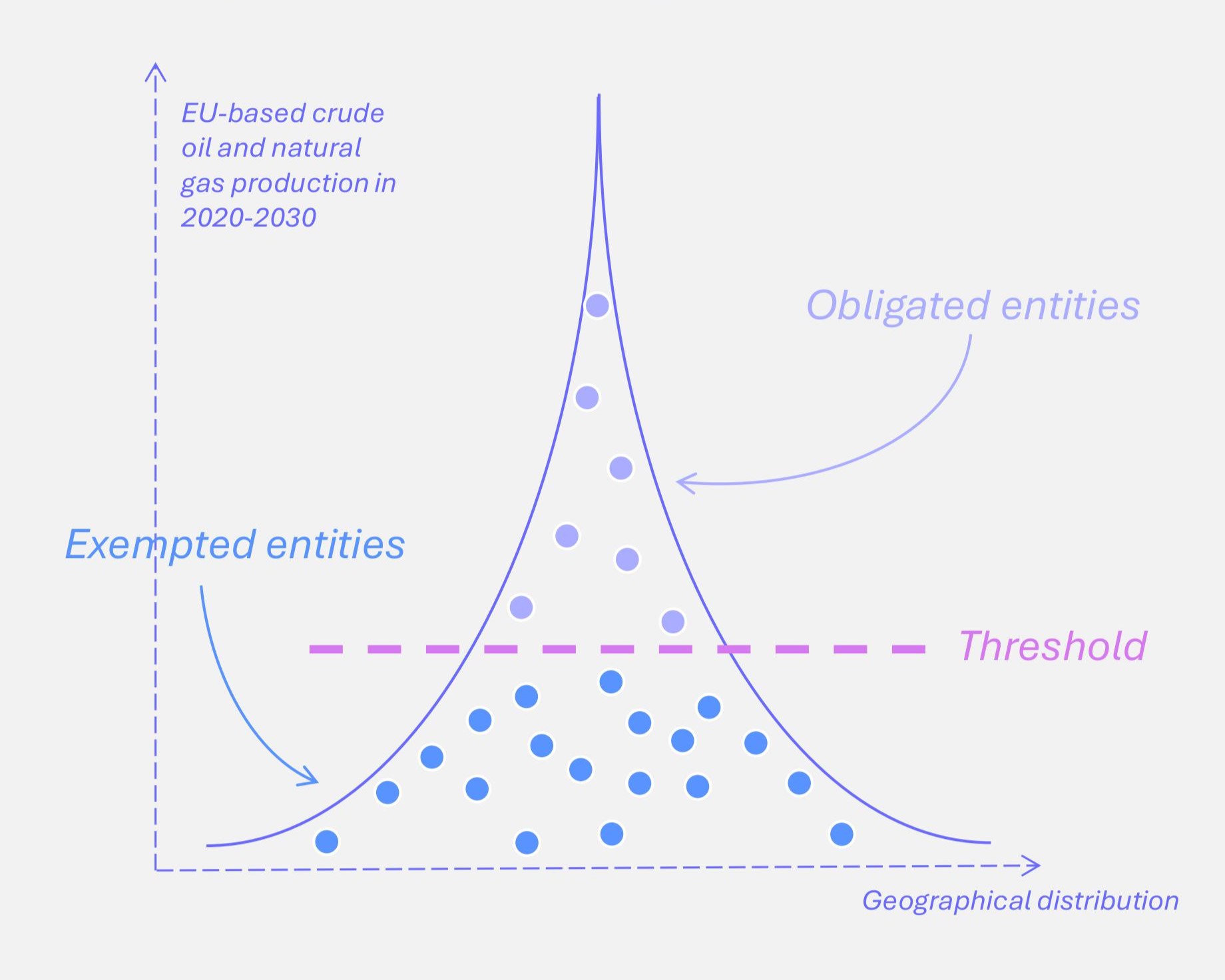

The ICO mechanism is imposed on oil and gas producers based on their share in the EU’s crude oil and natural gas production between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2023. However, a key issue is that the EU has hundreds of license holders with relatively small production volumes. To ensure the mechanism can be effectively enforced and the group of obligated entities remains manageable, a de minimis threshold with corresponding exemptions is therefore necessary (Figure 1).

However, this raises the question of where the de minimis threshold should be set.

On the one hand, a threshold set too low could burden SMEs lacking the resources to develop CO₂ storage infrastructure, while overloading national administrations with excessive complexity (Figure 2).

On the other hand, a threshold set too high could allow large producers with fragmented operations across Member States to potentially evade obligations, while disproportionately impacting smaller but locally concentrated producers (Figure 3).

As emphasised in our response to the Commission’s public consultation, it is crucial to strike the right balance when setting the threshold to ensure both fairness and accountability. The Commission has since adopted its final Delegated Act, which should enter into force at the end of July 2025, barring objections from the co-legislators during the two-month scrutiny period. The Delegated Act sets the exemption threshold at 610,000 tonnes of oil equivalent. It also specifies that authorisation holders whose crude oil and natural gas production between 2020 and 2023 accounted for less than 5% of the EU’s total production shall be exempted.

The calculated threshold succeeds in allocating responsibility in line with the principles of fairness and meaningful accountability. Covering 95% of EU oil and gas production maintains comprehensive coverage of the sector, ensuring that those responsible for most of the production play an active role in supporting CO₂ storage deployment across Europe. At the same time, it avoids overburdening small and medium enterprises (SMEs), while still allowing them to contribute meaningfully. In fact, exempted entities operating on CO₂ storage sites can participate as third-party storage project developers, fostering inclusive engagement across the value chain.

2. Identifying who is obligated

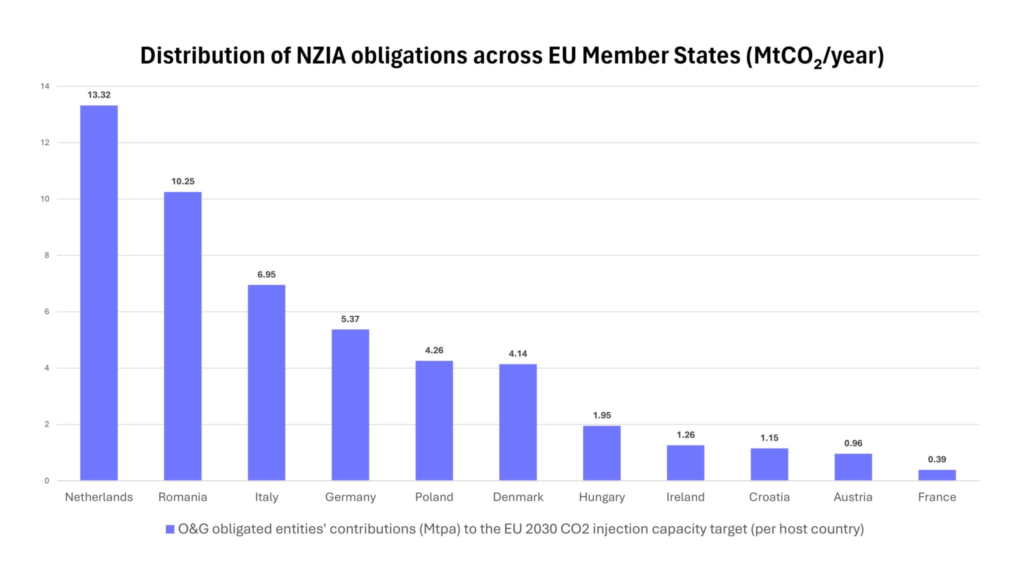

At the heart of the ICO mechanism is the issue of identifying the entities required to provide storage capacity and their respective shares. Importantly, the NZIA made clear that the entities to be obligated would be license holders, not the operators of oil and gas production projects. In accordance with the rules and calculation methodology set out in the Delegated Act, the Commission Decision provides a list of all the obligated entities and their respective share. The 44 obligated entities are located in 11 EU Member States: the Netherlands, Romania, Italy, Germany, Poland, Denmark, Hungary, Ireland, Croatia, Austria, and France (Figure 4).

Notably, the jurisdiction where each entity is located does not restrict those entities to fulfil their share in that same jurisdiction. As Article 23 NZIA outlines, obligated entities can meet their obligations anywhere within the EU, offering three compliance options:

- Invest in or develop CO₂ storage projects by themselves or in cooperation;

- Enter into agreements with other obligated entities;

- Enter into agreements with third-party storage project developers or investors.

This cross-border flexibility is key for countries without viable geological storage and incentivises regional cooperation.

3. Legal uncertainty remains a barrier to action

Despite the clarity offered by the Delegated Act and Commission Decision, several key issues remain unresolved. For example, while obligated entities are required to submit detailed implementation plans by 30 June 2025, Member States still have the possibility to request the Commission to exempt certain entities until the end of 2027 (subject to specific conditions). It is unclear how the exemption granted to one or more entities at a later stage could affect the individual contributions of other obligated entities, considering that they are directly derived from the non-exempted total EU production.

As ZEP highlighted in response to the Commission’s consultation, given the fast-approaching 2030 deadline, additional delegated acts clarifying the rules governing third-party agreements and the conditions for exemptions and derogations are urgently needed. The legal uncertainty spurring from this lack of clarity could jeopardise the successful implementation of the NZIA and impede progress towards the achievement of the storage capacity objective.

4. Systemic dependencies in the value chain could undermine compliance

While enabling CO₂ storage capacity in the EU is a clear focus of the NZIA, it is only one component of the broader CCS value chain. The development of potential CO₂ storage resources into operational projects relies both on the availability of sufficient volumes of captured CO₂ and on a transport infrastructure capable of delivering it to the site.

Given the complexities involved in developing the three parts of the chain, in addition to the other sub-parts, such as buffer storage, which typically involve multiple companies and projects, reaching final investment decisions (FIDs) for CO₂ storage projects remains a major challenge. In many cases, obligated entities may face delays in upstream infrastructure, such as CO₂ capture plants or transport modalities, whose availability is beyond their direct control, yet essential to developing operational storage projects.

Furthermore, advancing CO₂ storage resources involves lengthy permitting processes provided for in the CCS Directive, which is transposed into national legislation across EU Member States and the European Economic Area (EEA). In many cases, national legislation is outdated or simply prohibits the development of commercial-scale storage sites even in countries where obligated entities are present, such as in Germany and Ireland.

Moreover, in countries where developing storage sites is permitted, delays such as those experienced in the case of the Porthos project may be incurred, which could hinder the ability of obligated entities to comply with providing their share on time.

This interdependence creates compliance risks that have not been fully addressed in the existing Delegated Act. To ensure the effectiveness and fairness of the NZIA framework, the Commission should incorporate cross-chain risk mitigation into future guidance, recognising that CO₂ storage projects do not function in isolation but are part of a tightly linked industrial ecosystem.

5. Ensuring the ICO mechanism can work the need for greater action on CO₂ storage

As the Draghi Report and the Industrial Carbon Management Strategy (ICMS) underline, developing CO₂ storage is critical to ensuring Europe can reach its climate goals and its economic competitiveness. While the ICO mechanism recognises the role the oil and gas sector can play in providing CO₂ storage capacity, its effectiveness depends on greater action at the EU and especially national level to ensure that projects can reach FID and receive their permits on time.

Data from Member States’ annual reports show mixed progress on the status of CO₂ storage development and related infrastructure within the EU:

- Of the 18 Member States that reported back to the European Commission on the areas potentially eligible for CO₂ storage on their territory, 4 indicated none. 7 Member States published their database online.

- 16 Member States provided geological data for decommissioned production sites, among which 4 have obligations in place, and 2 are working on laws.

- 11 Member States reported a total of 62 ongoing CO₂ capture projects, and 2 Member States identified clear needs for injection and transport capacities.

- Only 9 Member States confirmed already having national support measures for CCS. 2 other Member States indicated they had introduced new measures.

This fragmented landscape highlights the need for supportive regulatory frameworks at national level to ensure accessibility to CO₂ storage resources for entities within the EU, especially considering that entities can only rely on EU-located storage to meet their individual obligations.

For obligated entities, several key issues thus still need to be resolved – from legal uncertainties and infrastructure dependencies to gaps in ambition at a national level. Without comprehensive policy support for capture, transport and storage infrastructure, the objective set in the NZIA to achieve at least 50 million tonnes of annual CO₂ injection capacity by 2030 risks being undermined. Closing these gaps will be essential and requires urgent action, not only for meeting our climate targets, but for maintaining the competitiveness of European industries in their pathway to climate neutrality.

Authors

Cristiana Foglia is a Policy Officer at ZEP, where she supports the organisation’s work on advancing evidence-based policy advice to the EU on industrial carbon management. She contributes to ZEP’s policy work, helping shape positions and recommendations on key EU files, including the CO₂ market and transportation infrastructure legislative initiative, lead markets (including the Industrial Accelerator Act), the Net-Zero Industry Act, the EU Climate Law, as well as International Environmental Treaties and Protocols (e.g. London Protocol)

A key part of her role is coordinating and consolidating input from ZEP members, translating diverse and technical feedback into aligned messages. She ensures ZEP’s policy outputs are technically robust, data-driven and clearly framed for engagement with EU institutions and other stakeholders.

Cristiana has a background in European and international law, holding a master’s degree in EU environmental law. Before joining ZEP, she worked in an environmental law firm in Italy, where she gained experience in EU and national environmental and climate legislation. Cristiana is an Italian native speaker; she speaks four languages and is passionate about EU affairs and climate action.

Aymeric Amand is Policy and Research Director at ZEP. He advises EU institutions and national authorities on industrial carbon management – covering the technical, economic, and regulatory dimensions of CO₂ capture, transport, storage, and utilisation, as well as of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) methods. He oversees ZEP’s analytical and policy outputs and represents ZEP in technical forums, including Commission Expert Groups. His expertise spans EU climate and industrial policy, carbon pricing, CDR governance, and EU funding instruments.

Aymeric also ensures feedback from industry, academia and civil society is reflected fairly in EU policy design. He helps build fair, workable compromises by weighing options against scientific evidence, project experience, regulatory requirements, and public-acceptance considerations. He promotes knowledge sharing and contributes to defining European R&I priorities for industrial carbon management. Trained in climate science, geography, and EU political science, he applies data analysis and GIS tools to quantify options and inform policy choices. He works in English and French.